Common Python Reference Cycle Patterns

In Python, when a set of objects constructs a reference cycle, none of them would reach a zero refcount. In this case, even if these objects all go out-of-scope and are no longer accessible, they will not be immediately released.

The Python ecosystem typically accepts reference cycles as an inevitable issue, and relies on garbage collection (GC) to avoid leaks. A GC is triggered by the Python interpreter from time to time; it will detect all non-reachable objects, and release them regardless of their refcount.

However, in high performance deep learning systems, GC is not always a good choice.

-

The GPU memory is so precious that we care a lot about its allocations and deallocations. We want a GPU tensor to be freed as soon as possible, and cannot risk leaving them non-reachable and wait for GC to kick in at a later time.

-

GC causes a random, significant pause of the interpreter. This is not acceptable for large-scale synchronous jobs, because once any worker is running GC, all others will have to wait for it in order to finish a collective communication.

Instead, high performance deep learning systems often disable the automatic GC, and run them manually at specific sync point, rather infrequently. See the relevant code in torchtitan and Megatron-LM for example.

Therefore a deep learning system engineer has to be aware of refcycles and avoid them. This post shares a few patterns of refcycles that are worth knowing. We'll also use objgraph to visualize the refcycle.

In this post, we'll assume GC is disabled, so that any object involved in a refcycle is considered "leaked".

Refcount and objgraph¶

Let's see a simple circular reference:

|

- The refcount starts at 2, instead of 1. This is normal as

getrefcountitself will also temporarily refer to the object. - Then we create a refcycle, the refcount becomes 3.

- We disable GC with a monkey-patch, because

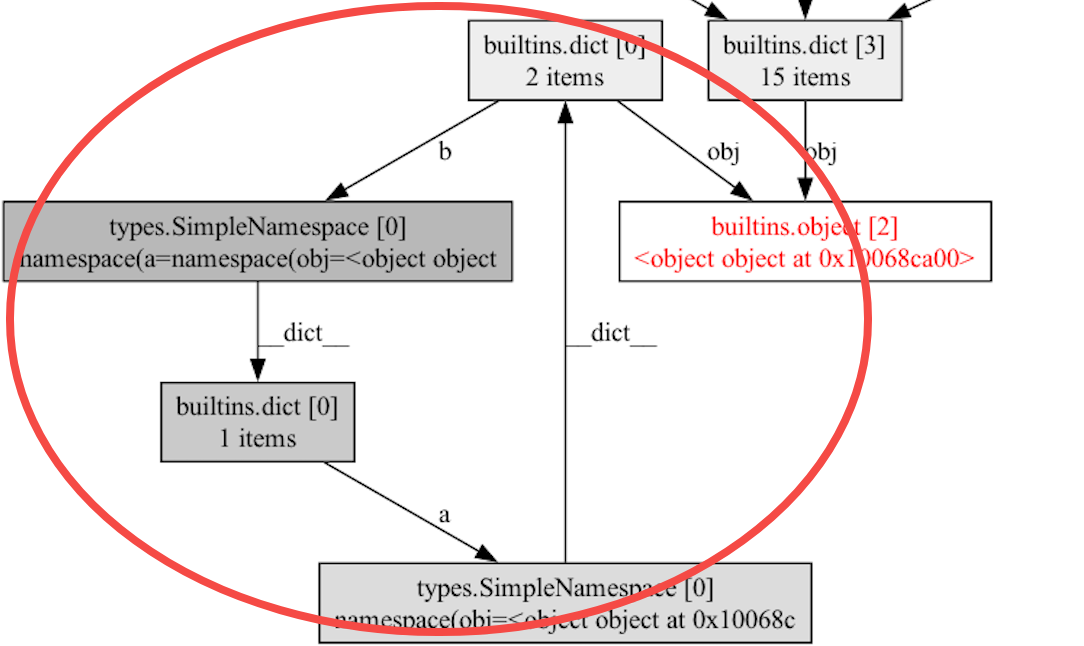

objgraphinternally would callgc.collectand remove our refcycle. - A reference graph is plotted which shows the refcycle:

Implicit references to self¶

In code reviews, I often frown upon any closure that captures self: when a closure

refers to self, we have to make sure self does not directly or indirectly refer to the closure.

Below is a simple example of a refcycle that may arise:

|

Any bound method also has a reference to self. So the following creates a refcycle as well:

|

The lesson learned from both examples is to prefer defining methods using the normal def syntax, instead of assignments.

Similarly, code below is an alarming pattern, because the active thread keeps a reference to self,

despite self owning the thread.

|

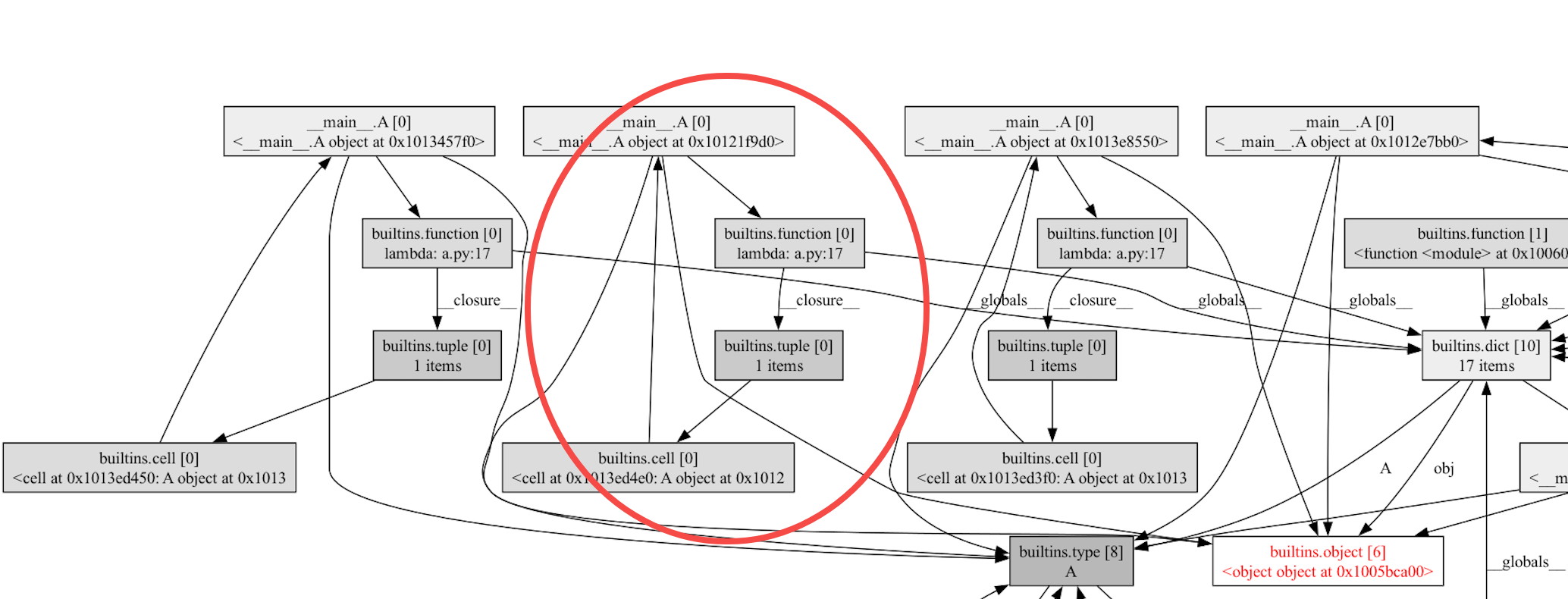

Recursive closure functions¶

In addition to capturing self, a closure that's a recursive function is also a refcycle by itself,

because it captures the closure definition.

|

In the example above, the function foo will leak because it refers to itself.

This is sometimes OK because a function definition is cheap.

But leaking foo causes obj to leak as well because foo refers to obj.

This could be a severe problem when obj is a resource-heavy object.

A simple fix to this example is to remove the function object from the local scope after using it:

|

PyTorch has seen a few similar bugs in the past where tensors get leaked due to recursive local functions. For example, [1], [2] and a more complicated one involving functions calling each other: [3]. @dzhulgakov recently posted another example on X.

Class definition is self-referential¶

Keep in mind that ANY Python class definition is self-referential -- i.e. any class definition will be leaked. This has been discussed in the CPython tracker a long time ago and hasn't been fixed. It is typically fine, as most class definitions are cheap, and they are created at import time and expected to survive the entire lifetime of the program anyway.

However, similar to recursive functions, it is a giant footgun to define a class that is a closure on local objects -- the local objects will be leaked. The following example demonstrates this:

|

This pattern has caused torch.save to leak memory.

The fix is also to set the class definition to None after use.

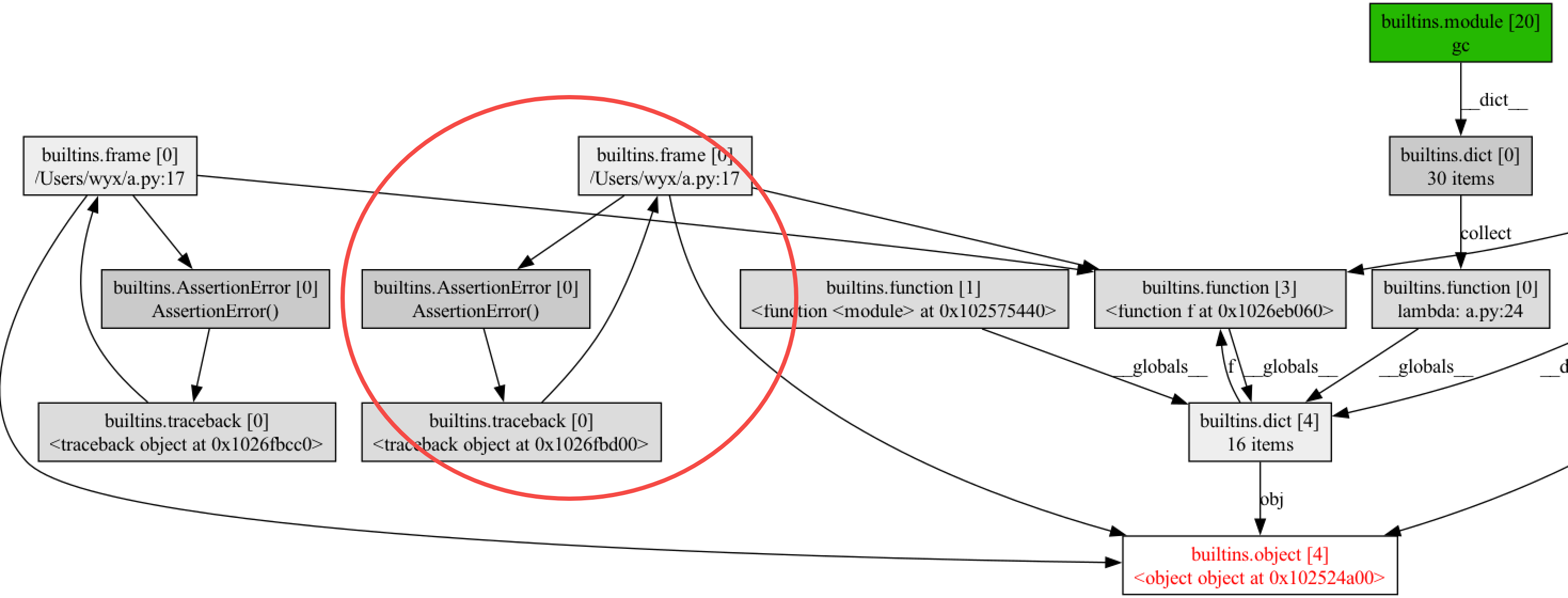

Exception refers to its stack¶

An exception stores its stack trace with all stack frames. Storing an exception object to a variable will create a refcycle "frame → variables of the frame → exception object → stack → frame". This leaks the exception object, together with the entire stack!

|

This is a big problem, because any library we depend on may have a seemingly innocent err = e statement,

and it will cause the entire stack that calls into this library to leak in a very hard-to-debug way.

This PR is an example where a 3rd-party library storing

the exception costs 100+GB of memory leak.

To properly store an exception, PyTorch provides a nice ExceptionWrapper that avoids refcycles.

See its comments

for details.

PyTorch autograd-related refcycle¶

In autograd, any tensor in the graph has a grad_fn that refers to a node in the autograd graph,

which may, in cases of custom autograd.Function or custom saved_tensor_hook, refer back

to the tensor itself.

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

are some bugs of this family.

What's worse is that the cycles involve C++ objects, therefore gc.collect() would not help.

The fix is to always apply a detach() whenever we need to manually save a tensor for backward

(even if the tensor does not require grad).

MagicMock and DictConfig are self-referential¶

A unittest.mock.MagicMock has some "magic" that allows mocked methods and sub-mocks (mocks created from a mock) to

access their parents. This introduces refcycles:

|

I attempted to fix it in CPython but it wasn't accepted.

Due to this issue, we should be careful when using mock in resource-heavy unittests (e.g. GPU tests) --

some intermediate results may get leaked.

omegaconf is a config library. Its config object is self-referential:

|

This is because it allows a sub-config node to access its parent. We should keep this in mind when storing any resource-expensive objects in the config.

More generally,

when any object has access to its conceptual parent/owner, i.e. if A owns B but B has access to A,

care has to be taken to avoid refcycle.

Ideally, we would structure software such that an owner has access to its children objects, but not the opposite.

But it is often not the reality.

Bidirectional access is helpful when flexibility is preferred, as we have seen in MagicMock and DictConfig.

As another example, detectron2's trainer owns several hooks -- which are functions to execute during training. These hooks themselves may need access to the trainer -- in order to access information about the training. A weakref is used there to avoid refcycle.

Summary¶

Eliminating refcycles is important in deep learning systems.

This post lists a few patterns of refcycle that I have seen frequently when debugging memory leaks.

When needed, objgraph can be helpful to identify refcycles.